Building Wokistan: A Peek into the Birth of a Banking System

In this post, I try to explain some concepts around money and banking by taking you through the early days of a new fictitious country. I try to start with nothing and build up to a more complex system. This isn’t necessarily a great subject for humor so I apologize in advance for attempting and failing.

A new country – Wokistan

For the benefit of my fellow millennials, let’s imagine a country Wok(e)istan that has just come into existence.

They have previously been involved in a barter-based closed economy – i.e no currency and no contact or trade with the rest of the world. Wokistan has only 10 citizens, all of them are single, unmarried and gender non-binary.

The people of Wokistan provide different services for one another using a barter system (farming, child daycare, haircuts – you name it). And Wokistan also has an abundance of Avocados. And turns out these are non-perishable Avocados – unusual indeed.

Of late, Wokistan has come to terms with the limits of a barter economy (A barter system might actually just work in a small place like Wokistan but let’s assume some “Eureka” moment arose, and the community felt the need for a currency (notes in particular).

The people of Wokistan come together to form the WCB (Wokistan Central Bank). They establish their currency the Wokistani Weenar – not the easiest on the tongue, so we’re going to shorten this to Weenar (I will assume this diminutive form isn’t offensive to anyone).

We’re going to assume that Wokistan, being a small, tight-knit community has achieved full consensus on the need for a currency (So we can rest assured that there is social and political will to move away from the barter system) In this case, since Wokistan has just ten people, the central bank is also the only bank.

Formation of the Wokistan Central Bank

To explain the first actions of the WCB, I will resort to balance sheet illustrations. This should be pretty easy to follow with a basic understanding of accounting

First order of business: The printing press of the WCB prints 1,000 Weenars (this is just an arbitrary number). At this point, we have no way to estimate or even intuit what this currency is worth. It’s been created out of thin air. However, for the currency to have any significance, it has to circulate through the economy and be worth something. Since currency is essentially a substitute for goods and services.

To achieve this, the WCB buys 1,000 non-perishable avocados (100 each) from its 10 citizens. Turns out everyone in Wokistan has access to Avocados and they exchange it for the Weenars (the new currency).

The citizens now spend the Weenars as they’d have spent the recently exchanged Avocado in return for other goods and services. Through these transactions, the Weenars start flowing the economy of Wokistan.

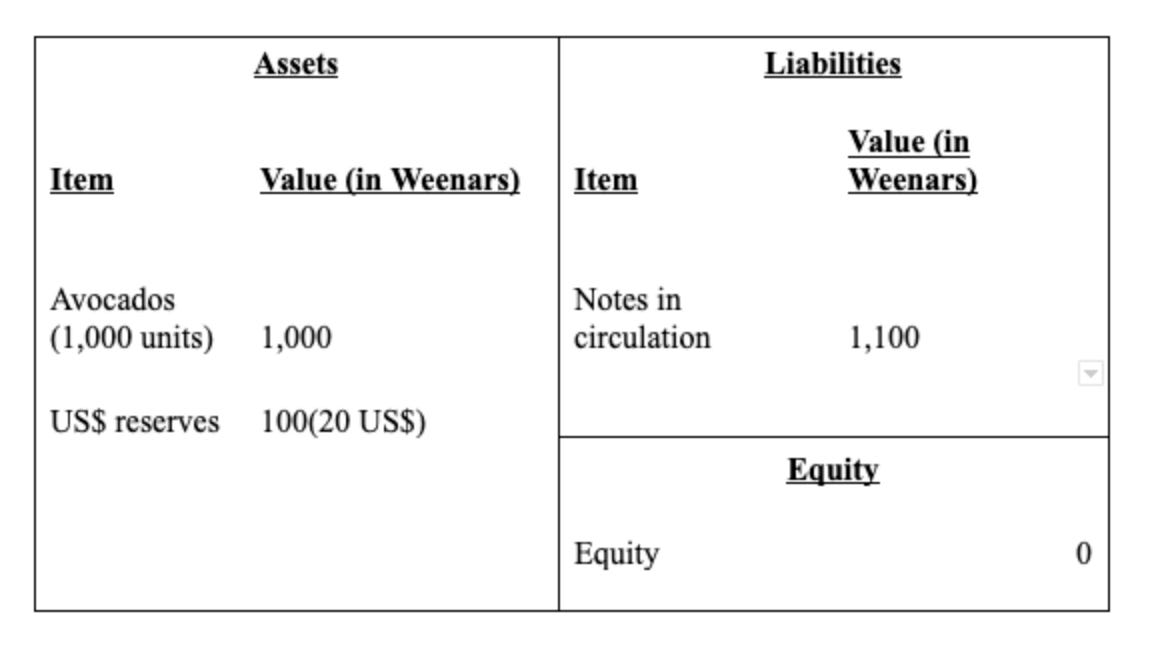

Let’s take a look at the balance sheet of the WCB after the printing of Weenars and the purchase of Avocados with these Weenars.

There are few observations to be made at this point

1. It’s worth noting that the notes printed by the central bank are a liability of the bank. This isn’t a trivial point. When the central bank creates money out of thin air, it’s not clear who it is liable to and why these notes are automatically a liability.

The intuition here is as follows: These notes, at the moment they are initially printed, have no value. They have value only in so far as they’re used to purchase asset or goods/services. So in this example, the central bank has acquired 1,000 avocados and paid 1,000 Weenars, establishing that 1 Weenar has the same value as 1 avocado.

So assume that 5 minutes after the central bank buys avocados, one of the famers changes its mind and returns the Weenars to the bank. In this instance, the central bank would presumably have to return the avocados – since they are equal in value. So in essence, the cash printed is a promise to pay avocados (or in a more general case, a basket of goods and services). This is line with our intuition of what a liability its– its an IOU – or a promise to pay. So when a central bank creates currency out of thin air, it instantly becomes its liability and its offset by the asset that it is able to acquire with its currency.

2. If the central bank claims that anyone can exchange an avocado for a Weenar at any point in time– it has established 100% fungibility between Weenars and Avocado, and fixed the value of the Weenar against the avocado. In other words, , the central bank has pegged the Weenar (to avocado). This is not different from the gold standard, where countries essentially backed their currencies with gold. Of course, they need NOT do this.

Wokistan is finally discovered….

Overnight, Wokistan is put on the world Map by a certain Columbus, who the Wokes hated instantly (and he was killed brutally by a barrage of Avocados but I digress…) Let’s imagine the world as it is today except that Wokistan has just been discovered. The WCB learns about trade and global capital markets etc.

Karen (an avocado farmer) learns that the world (especially northern California) loves non-perishable avocados, which can only be found in Wokistan. It gets in touch with an avocado trader based in Oakland, California.

The trader, being a half hippie half capitalist decides he will pay Karen up front. He agrees to pay Karen 20 USD for 100 avocados (At this point, this is what the market values non perishable Avocados in US dollar terms). Karen can only use Weenars in her local economy so she demands payment in Weenars.

The trader goes to the WCB to exchange dollars for Weenars.

Since the price of 100 avocados is 20$ and the central bank has just bought avocados for 1 Weenar each (previous transaction from its citizens), the central bank gives the trader 100 Weeners in exchange for 20 US$. At this point, we have the market exchange rate for USD/Weenar i.e – 1 USD is worth 5 Weenars.

Let’s take a snapshot of the central banks balance sheet at this point:

This example illustrates how a currency derives its value vis a vis other currencies. When a country offers something of value to the world, its currency derives value. So if we assume a country that produced nothing of interest to the rest of the world, we can safely conclude it would have no value with respect to other currencies.

This avocado example however doesn’t do justice to some of the other dynamics at play while determining exchange rate. Here are some generalizable insights:

The value of a currency vis a vis another currency is based on its relative supply and demand dyanmics. Assuming US$ supply and demand constant in this case the, value of the Weenar is driven by: (1) Supply of Weenars (controlled by the central bank and we can revisit this) (2)Demand of Weenars

Demand for Weenars in turn depends on:

Demand for goods and services produced by Wokistan

Demand from foreigners for land and other investments in Wokistan

Demand for Weenar deposits (not relevant in the simplified example but think about safe haven currencies like Singapore dollars or Swiss Francs or Japanese Yen)

Supply of money

Supply is where things get interesting. There are broadly two types of currencies:

Pegged Currencies

Freely trading currencies

Pegged Currencies

During the days of the gold standard, the US Dollar was pegged to gold. Today, some currencies are pegged to other hard currencies such as USD. A good example is Bulgaria where the Bulgarian Lev is pegged to the Euro.

How does pegging actually work (ok this is not a joke)?

Let’s assume Wokistan decided to peg its currency to the US$. This means, mechanically, the following:

Central bank announces that it will make Weenars freely exchangeable for US dollars at a fixed rate. Let’s use the rate from the previous example. 1 USD = 5 Weenars.

To satisfy this condition, every 5 Weenars must be be backed by 1 USD, so if the central bank wants to print Weenar (increase money supply), it can also do so if it acquire US $ in a fixed proportion

Let’s say a trader wants to buy goods from Karen again. To get hold of 100 Weenars, he pays the Central bank 20$ to get 100 Weenars.

Here’s the incremental balance sheet entry for this transaction:

This satisfies the condition we laid out: For every 5 Weenars printed, the central bank has acquired 1$ to back it.

IF it simply decides to print money without acquiring USD reserves, it will eventually fail to deliver on USD when people demand US$ in exchange for Weenars.

Note that we can substitute US$ for gold or silver or any other currency without changing the fundamental principle here, which is that the increase in money supply must be driven by the acquisition of another asset that the central bank cannot control directly. The ability of the central bank to acquire that hard asset (or hard currency) is in turn driven by real demand for the local currency by economic activity.

In this way, pegging a currency prevents the central bank from printing money and risking inflation.

There are two conclusions we can draw from this about pegged regime

Little to no fluctuation in exchange rate due to no arbitrade condition: This also means that the USD/Weenar rate will never fluctuate away from 5 for a significant period of time due to the no arbitrage condition. Let’s say for some reason, the USD/Weenar rate increased to 6, weaking the Weenar. A rational trader can buy the Weenar in the market and sell it to the Central Bank at a higher rate, thus pushing up the market price of the Weenar until it converges to 5. In other words, the central bank adjusts the supply of Weenars to keep the exchange rate constant, not withstanding the demand side of the equation.

Supply of currency adjusts to demand: Supply of the currency rises and falles in accordance with demand to keep the exchange rate constant

Freely floating currency

The alternative to pegged currencies is freely floating currencies. This means two things:

Central bank has control of the supply of currency and can increase and decrease the supply as they please without hard constraints imposed on it

The exchange rate can fluctuate based on supply and demand of the currency, since the no arbitrage condition doesn’t force the rate back to any fixed rate

US dollars, euros, Japanese Yen – are all examples of freely floating currencies.

Example of how exchange rates can fluctuate:

The affinity for avocados has reached far and wide, way beyond Northern California. Traders from around the world are now in touch with different avocado farmers from Wokistan.

Since non-perishable avocados are exclusive to Wokistan, traders from around the world are competing to buy the finite number of avocados from farmers in Wokistan. A consortium of farmers now sell 50 avocados for 20 USD (this is twice the price at which they sold previously).

So the price of non-perishable avocados has gone up from 20 US cents to 40 us cents per avocado. The WCB notices that this is a good time to build more US$ reserves. It now sells 200 avocados off its balance sheet to a trader for US$ 80 (0.40$* 200).

Let’s analyse the balance sheet after this transaction without assigning Weenar values to the left side of the balance sheet.

The left side contains 800 avocados and 100 US$. The right side is the same – 1,100 Weenars. We now have a way to calculate the new implied exchange rate.

Notice why it’s important to do this. The avocado has suddenly become more valuable relative to the US$. We’re trying to figure out how that affects the relative value of the USD/Weenar.Equating both sides of the balance sheet:

800 avocados + 100$ = 1,100 Weenars

We know that 800 avocados is worth 320 $ ($0.4*800) based on the most recent market price of Avocados in USD.

320$ + 100$ = 1,100 Weenars

420$ = 1,100 Weenars

1$ = 2.6 W.

The Weenar just got stronger.

It’s important to intuit why this happened.

The implicit assumption here is that Wokistan, cordoned off from the world, is able to produce Avocados. As a result, the central bank of Wokistan had avocados on its balance sheet. As these Avocados became desired by the world and their value increased and in turn the demand for Weenars.

Since the central bank did not increase the supply of Weenars in response to higher demand, it inflates the value of the Weenar vis a vis the US dollar.If this had happened in the pegged system, there would have been no appreciation – the central bank would have just printed more Weenars to keep the exchange rate constant.’

This is a good primer on central banks and some of the different ways they can handle currency. What do you think of pegging as a way to combat inflation?