So you think you can lie?

“Have you ever cheated on someone?” a date once asked me. I responded in the affirmative, choosing to spare her the etiquette lesson and revealing to her something I had previously withheld from the “someone” in question. In fact, I didn’t have a choice. I had recently committed myself to a 'no lying' policy, inspired by a second reading of 'Lying' by Sam Harris, a book I had previously enjoyed but refrained from internalizing. Before my commitment to honesty, I wasn't a habitual liar. My lies were mostly akin to minor social adjustments: rescheduling plans or skirting around a grueling corporate job. However, I had my share of significant falsehoods, one of which was indeed related to the question posed by my date. By confronting my past misstep that evening, I sat with the discomfort that honesty often entails, reluctantly reflecting on the costs of my previous departures from honesty. But her question also provoked a reflection on why a policy really was necessary.

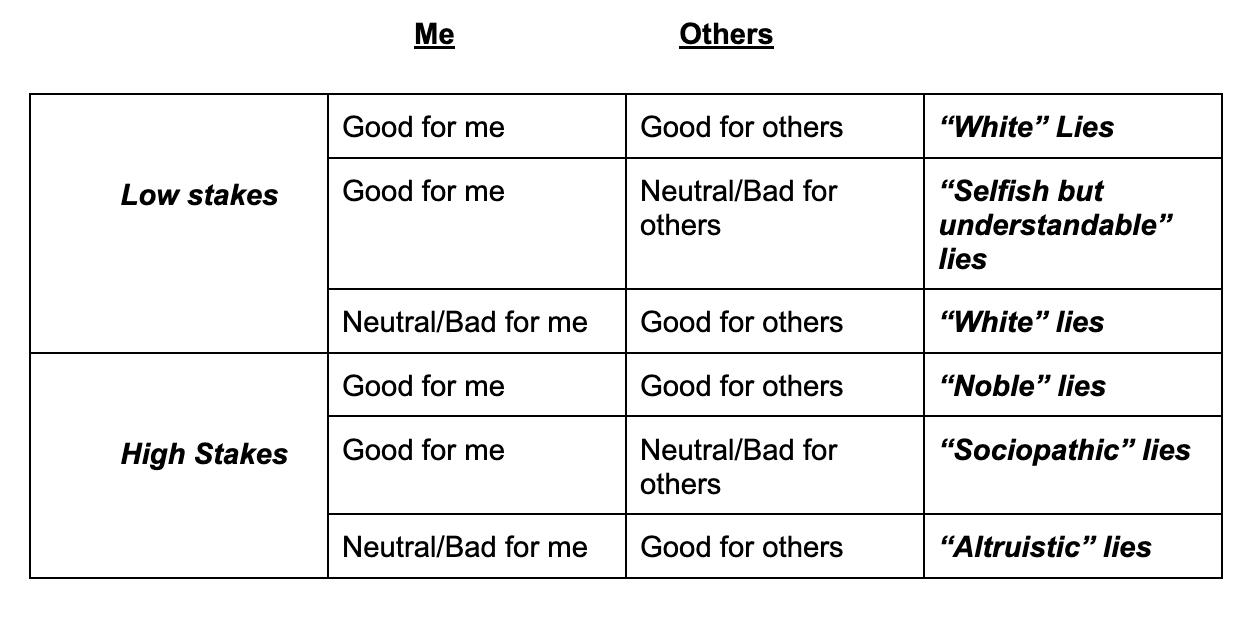

A significant proportion of the lies we tell are mediated by little to no conscious thought. Let’s set that aside for now to understand the categories of more considered falsehoods that are preceded by a somewhat conscious cost-benefit analysis. From the perspective of the person telling the lie, they fall into six categories, based on whether it’s perceived to be low stakes or high stakes, and whether those consequences are expected to be positive or negative for those lying and those being lied to.

With this in mind, I want you to meet Joe, a married man who got shitfaced last night and slept with a stranger. Joe is not “cheating Joe” - this is the first time he has swayed from a monogamous arrangement. He feels terrible about his indiscretion and confident in its one-offness. He knows telling the truth is likely to cause his wife deep anguish. Joe, who has identified as a nice guy all his life, does not want to cause anguish. Joe knows lying is generally wrong, but what good could come of the truth anyway? Joe would rather be a good person and live with guilt.

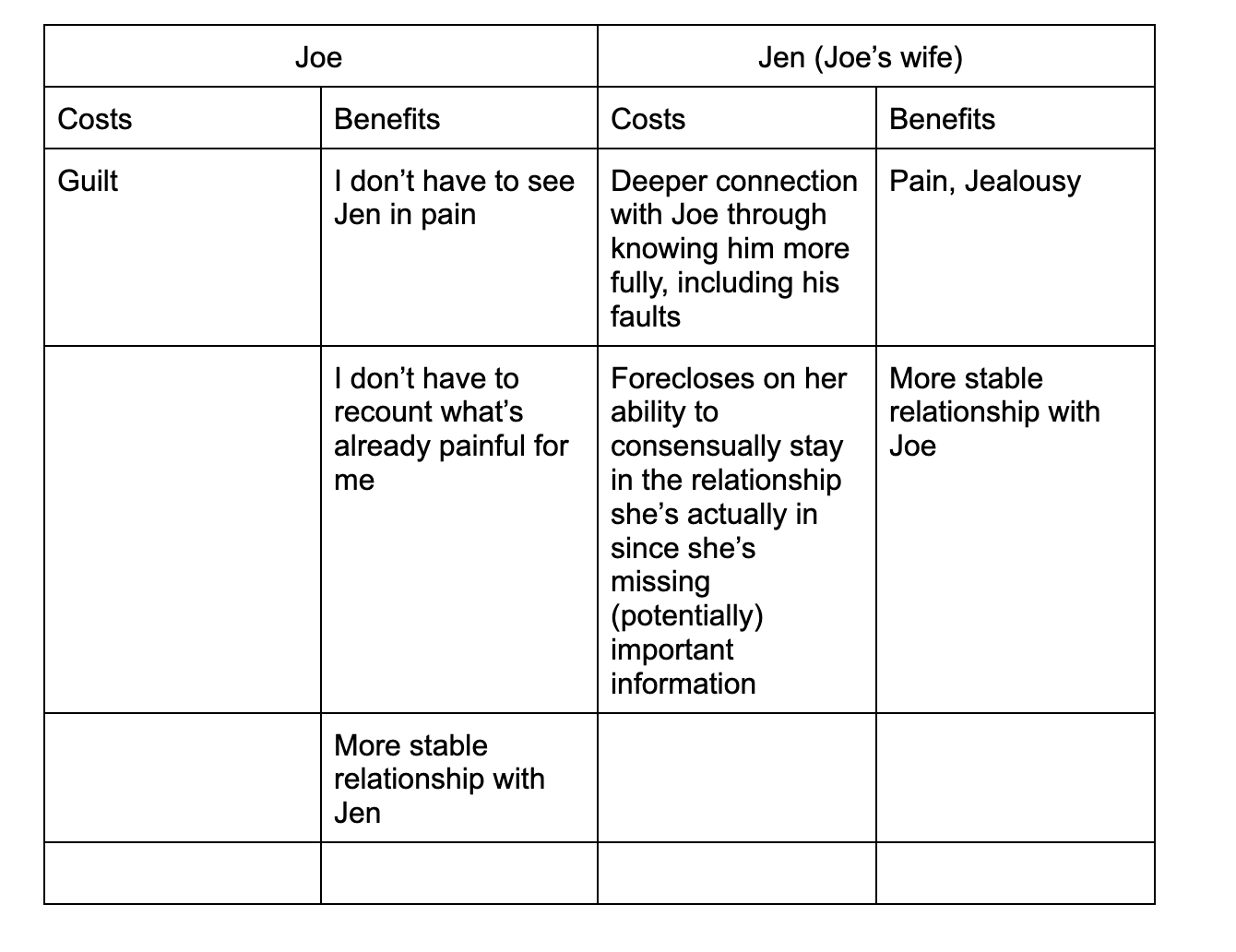

Assuming he doesn’t tell his wife Jen, here’s what Joe’s cost-benefit analysis could look like in his head:

Joe’s cost-benefit analysis indicates that by not revealing his adultery to Jen he is telling a “noble lie”, but his analysis is incomplete in a couple of important ways. Consider this - Joe’s wife, Jen, might be a better judge of what’s in her self-interest. Perhaps, Joe doesn’t have the most accurate conception of how happy their relationship is. Perhaps, she’s been perturbed by Joe’s drinking and is on the fence on whether to leave him anyway and this information might be important to her. Perhaps, her estimates on “How likely is Joe to do this again?” look very different from Joe’s estimates on “How likely is Joe to do this again?”. Robbing her of that choice should certainly go on the costs side of the equation.

More importantly, Joe is unlikely to see this clearly, since he’s benefitting from this lie in an insidious way. Joe has avoided having a deeply painful and confrontational conversation - one in which he has to be fully present to the pain his actions have caused and reconcile the consequences of his actions with his self-conception - of being a nice guy, a good partner etc. Can Joe be confident in the objectivity of his analysis? We all know and acknowledge our proclivity to overweight short term discomfort, often privileging it over our own longer term hopes, dreams and ambitions. It’s likely we’re not beyond privileging it over a loved one’s either. Here’s a more complete picture of the situation:

This isn’t to say that the cost of having this conversation is so high for everyone that it categorically overrides every other consideration. But that we are highly capable of crafting an unlimited number of plausible stories to spare ourselves short term discomfort. We tend to be generative creatures while coming up with reasons to avoid activities that cause pain and risk the slightest perturbation to our dear friend, inertia. Whether it’s going to the gym or ending a toxic relationship, we just don’t seem to like this stuff very much.

This is why honesty is better thought of as a habit - something that has to be actively practiced and cultivated, so as to make it our default. In his book “Lying”, Sam Harris presents a compelling case against white lies and honorable lies, concluding that they’re not as innocuous or as principled as they seem when you consider the long-term consequences to your interlocutor, your relationship with them, and your own reputation. I don’t doubt that you can come up with edge cases where white lies truly have positive expected value. But cultivating honesty as a habit seems likely to lead to better decision making in the future which will more than compensate for the loss.

Does this mean there are no situations where a lie is warranted? Probably not. There could be exceptions, for instance, when you're interacting with people whom you don't trust to act in good faith. However, even in most of these scenarios, lying is not obviously the superior choice. If you're genuinely committed to the pursuit of honesty, a strategy might be to include a safety net in your moral framework. This could take the form of a small, trusted circle of friends, people who are wise and have shown serious commitment to their own ethical principles, even if they don't exactly align with yours. Make it a rule that before you decide to lie, you consult with at least two or three of these friends. This not only imposes a significant cost to lying - thus making you reconsider whether it's truly worth it - but also provides an external perspective, which can often be more objective. This check-and-balance method helps ensure that if you ever do deviate from the path of honesty, it's after serious consideration and consultation, not merely a reflexive action to avoid discomfort.

Believing at the time that I was sparing both myself and my partner from unnecessary pain, I chose to withhold the truth. But with distance and time, I see egoism, not nobility. in my decision. Just like Joe, I had given in to my desire to control her perception of me and the trajectory of our relationship. As I read Lying and reflected on the past, I felt driven to transform myself into a person who would never repeat that mistake. My current partner, who knows this story in excruciating detail, thinks I'm not far from being that person. Awkward dates seem like a small price to pay.